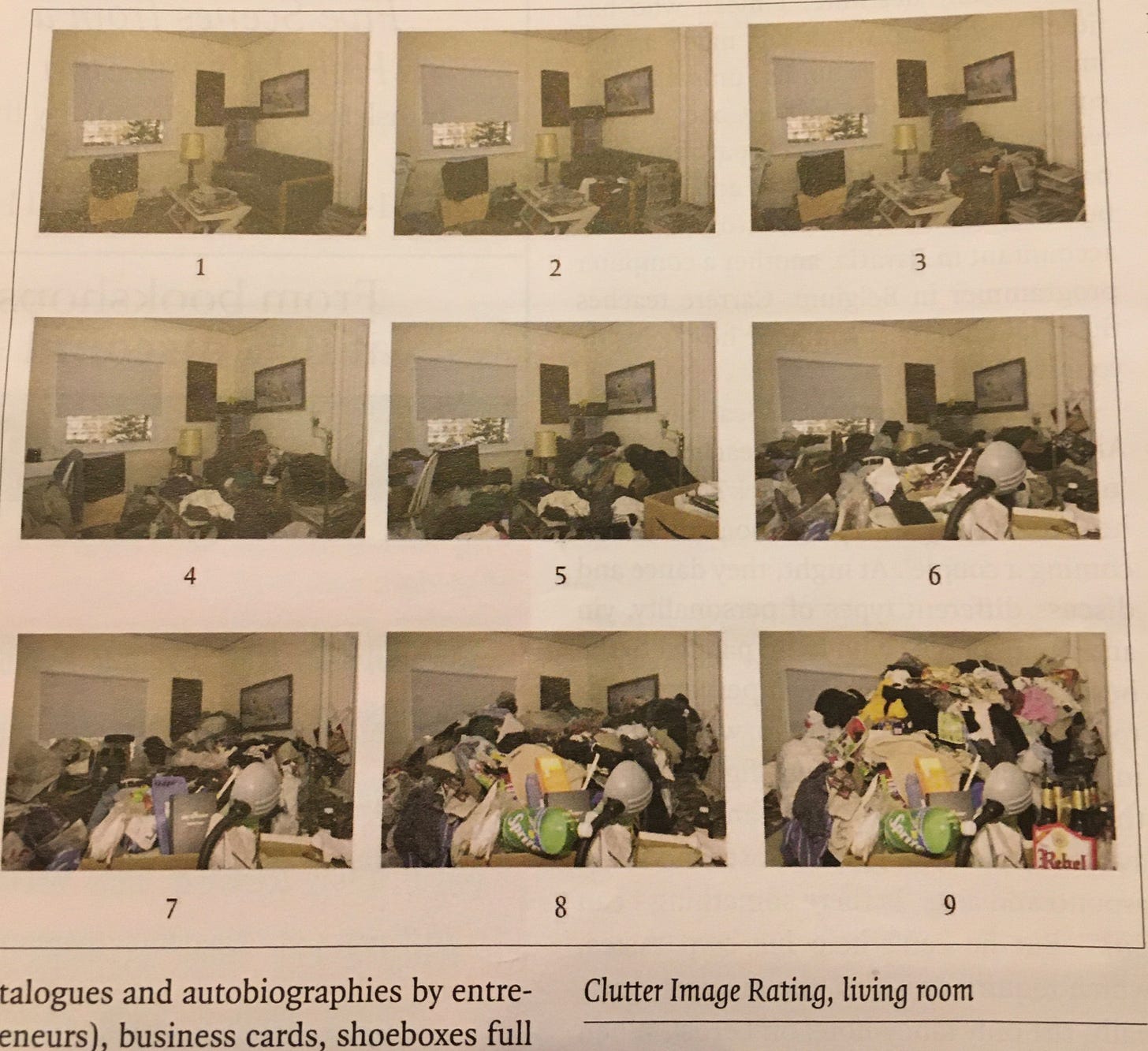

These diagnostic images accompanied a London Review of Books “Diary” essay by Jon Day about hoarders. They are meant to provide an objective baseline for evaluating the severity of pathological hoarding, but they immediately struck me as a metaphor, a time-lapse series capturing the evolving condition of my mind on any given day as it precedes. Usually I wake up with an orderly sense of where things belong and where things can be found, but soon the room fills up with an unruly pile of garbage that I eventually give up on trying to sort or discard. I know there were ideas buried in there somewhere, but I don’t think I will be able to find them, and who’s to say they wouldn’t have just become someone else’s mind trash?

“Hoarding,” Day notes, “is a modern malady.” It stems from the superfluity of “cheaply produced goods” that allow us to live primarily as consumers, with a blurred sense of the use value of objects. Everything functions as a collectible as well as whatever purpose it ostensibly serves. Consumer society presupposes a satisfaction in shopping as an experience, in acquisition for its own sake, regardless of the specific things involved. At a fundamental level, routine participation in the circulation of goods is what allows one to feel like a valid and useful member of society; even when that participation takes the form of “purging” or abstention, one remains oriented to the centrality of commodities to life’s purpose, figuring out how to manage their flow through the spaces one occupies and how to make space for more, and for the social relations that are acquired and processed as things.

Hoarding is one way to accommodate oneself to a quantified life, an attempt to maximize one’s score. But then again, any maximizing, economistic approach to living becomes a kind of hoarding as the means and ends reverse and it tips over into irrationality. It’s hoarding when I keep opening tabs, when I try to get to the end of my RSS article queue, when I use iTunes play counts to organize my listening habits, when I buy books I won’t live to read, when all emails and chats are automatically archived. Amid all the mechanisms for turning experiences into various forms of data and media, into alienable quantities, I find it harder to have a purely qualitative relation to anything; I begin to understand “quality” as simply the effort of resisting quantity, as something understood only after the fact, as when one loses track of time.

Quoting from Possessed, a 2021 book about hoarding by Rebecca Falkoff, Day suggests that hoarding “is always in part ‘an aesthetic problem,’” in part because the pathology manifests visually, presenting abundance not as a dream come true but as a total mess. Hoarding makes chaos out of the idea that one can have everything one wants; it bluntly demonstrates the contradictions inherent in that fantasy. It’s deeply unnerving to be around other people’s hoards because, in a kind of immersive imminent critique, they call into question our own motivations and rationalizations about what we have and why we have it, what it is all for. I’ve often had this experience looking at someone else’s massive record collection, where the comprehensiveness of it reaches a kind of sublimity, and I start trying to think of a record they don’t have, as if that were the only music I would want to hear. I’d have this spontaneous fantasy of giving all my records away and becoming one of those people who is happy to listen to the radio, because there is still a fleeting sociality built into it, an unconditional surrender.

For a while, it seemed like the social media fad for aesthetic minimalism worked as a kind of determinate negation of hoarding, but those pristine spaces were compelling in part because one could take their clean orderliness as a license to imaginatively clutter them. After seeing enough of such images, they produced their own feelings of suffocation. The hoard was there in them, inverted, a no less oppressive accumulation of blankness. Their low density of information was not for its own sake but optimized to yield a different sort of surfeit, to allow so many more minimalistic images to coarse faster through so many media feeds. The disorder was displaced from the images’ content to our scattered sense of attention.

In the preface to Possessed, Falkoff likens physical hoards to the hoard of images she had compiled on a Tumblr called If I Were a Hoarder. “The blog distended haphazardly to include virtually any digital content I stumbled upon that seemed somehow relevant,” she writes. “Hoarders mingled with ragpickers, gleaners, scavengers, misers, fetishists, collectors, archivists, and makers. Discussions of academic works of new materialism, historical materialism, discard studies, and thing theory were punctuated by images of abandoned objects, cabinets of curiosity, and cluttered spaces.” She found that “the unwieldy accumulation of content reproduced the logic of a hoard,” which she defined as “the ceding of authorial or curatorial intention to a series of chance encounters with miscellaneous stuff.”

(That logic characterizes what, by default, I have to describe as my “method” in writing, since I have never been able to organize a research project or sustain a specific focus for longer than it takes to put together a blog post. I keep thinking that one day I will take on a “real” project and change my ways; that I am writing this suggests otherwise.)

In the early 2000s there used to be a sense that “digital consumption” would be an immaterial alternative to amassing things, that it would generate a liberating “post-scarcity” mentality that would detach personal identity from possessions and open up new realms of experimentation in who we could be. Instead, objects, images, and experiences began to merge together; consumption became self-production in an even more direct and concrete way. Identity itself became more definitively reified as a personal possession. Consumption was even less about the pretense of satiating basic necessities and more about its documentation: consuming oneself consuming from the imagined, required point of view of envious others. Consumption could be conceived as an ongoing stylized performance, typified for example by the phenomenon of "photographable food.” This mode established an idea of the self as a collection of self-made souvenirs, a growing hoard of self-conscious moments piling up in the mind’s self-storage facility.

A similar promise of liberation sometimes seems to lurk in the extravagant claims made for image generators like Dall-E, Midjourney, and the most recent addition to the pantheon, Stable Diffusion. Amid the fears that they will somehow make artists superfluous (they can’t and won’t) is an implicit hope that they are the first step toward making something like the Star Trek replicator. After all, we have been training ourselves through media to reduce the distinction between an image and the “thing itself”; if a machine can make an image of anything we can think of, that is almost tantamount to having everything our hearts can desire. But it also means that it is yet another emergent hoarding nightmare. When I went to try out the Stable Diffusion “dream studio,” I found myself confronted with a blank prompt and the limits of my imagination, the very thing image generators are supposed to make beside the point.

Hoards of images in data sets lie behind these models, and the prompts are indirect and inefficient probes for exploring them. This site allows you to explore those hoards in a different way, allowing you to check to see if a specific image is in a training set and to see which sort of images are associated with specific queries. I searched my name and saw lots of faces, none of them mine. I was relieved but also wondered if that meant I was missing out on a new kind of mediated social inclusion, a different way to listen to the radio.

AI generators still have obvious practical shortcomings and biases, but despite (or because of) this they are poised to overwhelm the available channels with fabricated images that newly commodify something that we once largely took for granted, the basic linkage between ideas and their concepts. These models relentlessly seek identities between words and things, assigning weights to their probabilities, eliminating present consciousness from the process through an increased quantification and fine-grained analysis of the past. We may end up disincentivized from imagining new possibilities, from exploring that nebulous negative space, deferring to machines to establish or confirm these links, to dictate the horizons of the known.

The recent viral thread about Loab, the supposed demon lady lurking in AI generators that Max Read describes here, could be understood as the haunted face of this possibility, what it looks like when we can’t imagine things for ourselves and are fully subject to prefabricated horrors. “Like any cutting-edge technology, AI also has a tendency to reflect back our anxieties,” Read writes. “AI anxiety has to look like something.” Loab could be understood less as some specific being than a distillation of all the potential images that the generators will make, the implied destination in all these imaginative leaps being made mechanically, that we will feel obliged to collect rather than think into being. Loab is a clutter image as a face.

Sad to see RL go but glad something is coming from the ashes.

This has me thinking about what I don't collect/consume (something I often thought about while reading RL). Ironically, I find that physically consumable things often provide a less immersive experience than digitally consumable things. And where's the in between?

I’m struck by how heavily the image at the top is weighted toward the high end of the scale. Once you get to about 6 or so, are further distinctions particularly illuminating? If the trash pile reaches 6 feet instead of 5 feet, I’d say that’s more indicative of the hoarder’s *height* than pathology at that point...

Anyway, great piece.