Crosscurrents

is it worthwhile to read meaningless text

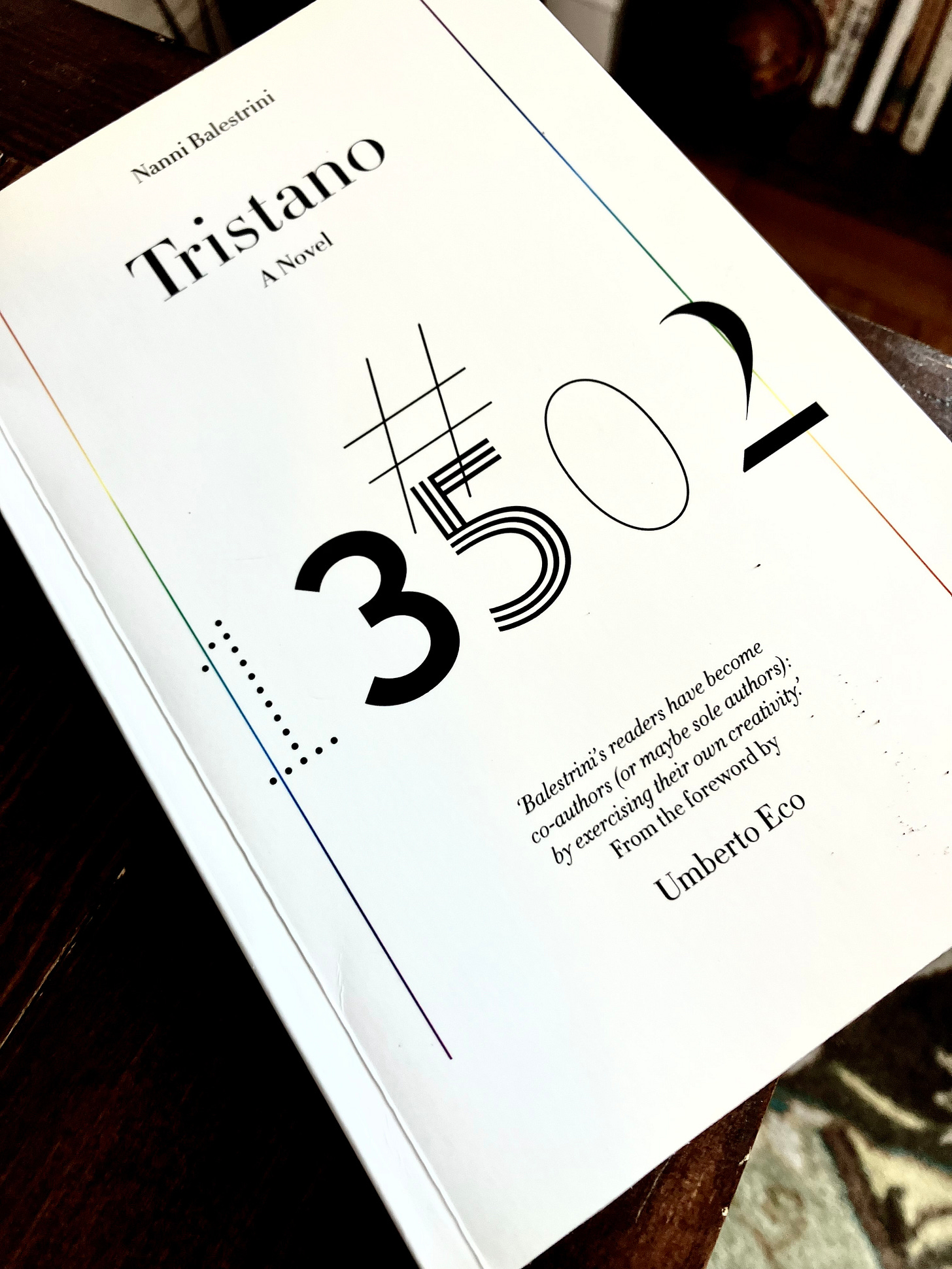

Recently I decided to read Tristano, an experimental novel by Nanni Balestrini that was conceived in 1966 as a work that would be published with each individual copy containing its own unique sequencing of the 200 or so paragraphs that comprise it. Publishing couldn’t easily accommodate this concept until recently, but it was realized in an English language version by Verso in 2014. In the introduction, Umberto Eco calculates that there are something like 109,027,350,432,000 different possible versions; mine is No. 13502, according to the figure on the cover.

I bought my copy a few years ago, during the heyday of NFTs, in part because it seemed like the point of it was to be “nonfungible” — to take a mass-produced object and occult it with an schematized variation that made each “copy” also singular in its own right. It seemed like an objet d’art meant to be mused over as a provocation rather than actually read.

But the rise of LLMs has given Tristano a different kind of potential relevance as an early example of a text that has been generated rather than written, inviting readers to consider what effects this has on one’s attempts to read it. It was conceived during the structuralist, “death of the author” theory era, and it raises the same sorts of questions: Should the reader be considered the “author” of a text (see Eco’s blurb on the cover) because they are doing the work of reading a purpose into it? Can such a text can be “understood” at all, given that it can’t be located within a horizon of interpretation? Is any text ever understood or are all readings of them ultimately arbitrary, unanchored, dependent on a “master signifier” that is absent? Is there any point in talking about plot, characters, settings, and rhetorical effects under such conditions, where “authorial intent” has been put under erasure? What is left of “the novel” once its social existence has been thoroughly undermined?

It’s perhaps trite to argue that every encounter between a text and a reader can be described a unique singularity. Depending on their context, their mood, their attention level, the order in which they read, the amount of text they skip, and the level of mastery they have over the language in general, readers activate texts in different ways with every reading. Tristano makes this point seem both more obvious and less significant. “A spoken story changes more or less when told to different listeners, or at a different time, Balestrini writes in his introduction. And in this way a literary work, a novel, can be created, thanks to new technologies, no longer as an immutable unicum, but in a series of equivalent cariants, each materialized in a book, the copy and personal story of each reader.” But with a text that no one else sees, the stakes of that “story,” if it can still be called that, are wholly solipsistic — an assertion of that singularity of the encounter for its own sake. Each is “a slightly different variant of a nonexistent prototype,” Balestrini suggests.

Writing about “intelligent machines” in The Transparency of Evil, Baudrillard suggests that “if men dream of machines that are unique, that are endowed with genius, it is because they despair of their own uniqueness, or because they prefer to do without it— to enjoy it by proxy, so to speak, thanks to machines. What such machines offer is the spectacle of thought, and in manipulating them people devote themselves more to the spectacle of thought than to thought itself.” While that has obvious applications to the nitwits using Chat-GPT to have it tell them how smart they are, it’s also a bit of what it felt like to read Tristano — like I was acutely aware of having a unique experience that seemed to consist of little but its being unique. As I read it, I was performing the idea of reading it because that is all it permitted.

It’s one thing to think an intention-less text and the issues that raises in the abstract, and another to experience them over time as you work your way through a text that frustrates attempts to pin it down. You can’t test your reading against anyone else’s, so you are largely free to interpret it however you want, but this is overshadowed with a general sense of the pointlessness of looking for any meaning at all when it will be shared by no one and none was originally intended by anyone, at least at the level of the sentences and their sequence. Tristano lures you into trying to close-read the text to make some sense out of it, but you immediately remember that there is nothing to be revealed, no right answers, just a bunch of semantic Lego blocks or magnetic-poetry strips whose arbitrary arrangement you can try to rationalize in your mind, even though no one else will be able to confirm your ingenuity (unless you make them read your copy).

Before reading it, I thought Tristano might have something to do with Lennie Tristano, the jazz pianist who was a pioneer in free improvisation and one of the first to use multitracking and overdubs to construct his recordings, but Balestrini says in an introduction that the title is a “ironic homage to the archetype of the love story,” Tristan and Isolde. As it turns out, there are no characters in the novel called Tristano, and of course there is no narrative flow, though the sentences often have the air of evoking a mise en scène of some sort. Some of it is in first person, some in third. Since their sequence is arbitrary, individual sentences tend to stand alone and establish a mood of their own, piling up like pieces to a jigsaw puzzle with no solution. Anything can be read literally or metaphorically; it makes no difference. Each paragraph reads a bit like a fragment from an Alain Robbe-Grillet nouveau roman — blank, mostly descriptive prose that is difficult, or impossible in the case of Tristano, to locate within a character’s consciousness or associate with a particular point of view.

As far as I could tell, there are three or four people in the action recounted in book; they are frequently described in taxis, hotels, or airports, and maybe some archaeological sites, having disjointed conversations full of non sequiturs that can be as pregnant as you want them to be. For some reason commas are not used. In reading, I had to teach myself not to care about the kinds of things I normally read novels for — aspects that shed light on the author’s aims — and instead let my eyes skate over the surface of the text, letting the phrases spark whatever kinds of ideas in me. Here are a few consecutive sentences from my edition, to give you a sense of it:

She fell back onto the pillow and lay there gazing up at the ceiling. He had a limp in his right foot. It’s not cold anymore. At a certain point. They walked together on the pavement where the sun was not shining until the end of the street.

It’s not as though these sorts of lines can’t be seen as “poetic language,” full of unresolvable semantic potential, ambiguous and multivalent, portentous without evoking anything definite. Sometimes the sentences seem like metafictional comments: “I could not add anything here other than my previous observations. He was looking for another story to tell.” “One must be open to the thing that is being born that is shapeless magmatic it seems like it resembles life.” “Upon reading these various extracts they not only seemed to me irrelevant but I could perceive no mode in which any one of them could be brought to bear upon the matter in hand.”

But any conclusion about what they might signify is always absolutely provisional, ad hoc. Part of the point of Tristano is that all language use is just that: radically undecidable in the last instance, with meaning endlessly deferred down the signifying chain. But that view, taken to its extreme, also means communication is basically impossible and not worth attempting, and one may as well see oneself as the “author” of everything because you have some inevitably unique way of parsing the signifiers involved.

I found it extremely tiresome, and tiring, to be “co-authoring” Tristano as I read it, and I started skimming faster and faster as I flipped through it. There was no suspense, no tension, no need to wonder whether I was wrong about what I thought was happening on the page. Maybe I failed to rise to the occasion, as I often do with experimental literature, but I progressively became lazier, surrendered more and more of my criteria for what makes a passage worth reading carefully, and instead just let the words flow by, grateful that I could see there was an eventual end, even if it would come with no sense of closure.

But the experience did make me wonder why people reading generated text don’t have a similar experience. In some respects, chatbot blather is pretty similar; it’s uninterpretable with respect to an ultimate intention, and any ambiguity in it seems ever more vertiginous, uncircumscribed by any reference to another’s consciousness of it, to any intention, unless you regard the underlying statistical model not as a black box but ultimately knowable, verifiable, some kind of proxy for “what a text should say.” You might even argue that the statistical model is more limited than the human use of language, which truly is unpredictable and entirely open-ended, unless you accept the principle that no new combinations of letters can be invented that haven’t already been modeled as more or less probable given a certain set of datafied conditions as a reference point.

Nevertheless, why do so many people seem to want their reading of an ungrounded intention-free text-for-one — their “conversation” with a large language model — to go on and on? Why subject your brain to an extended exposure to meaninglessness? Why do many teens, at least according to this survey, find it preferable to conversation with other people? Obviously there are also big differences between chatbot sycophancy and avant-garde literature, but maybe the most salient one is that a chatbot always affirms your interpretation of its words and literature offers you no such support. Reading Tristano I was overwhelmingly aware that no matter what my interpretation was, I couldn’t possibly be right. Using chatbots seems to promise the opposite: No matter what you say, they make you feel like you couldn’t possibly be wrong.

I would feel tempted to cut up the text and try to rearrange its paragraphs in some order that might approach the coherence the lack of which you found so tiring. Or to browse it randomly with such an aim of linking, marking the order of reading as numbers in the margins.

Running internal commentary as I read this: Erasure poems / Being John Malkovich / Into the Spider-Verse / Batman vs Superman / Choose no one's adventure.