Just for a second I thought I remembered you

Being compelled to ask yet again, Are friends electric?

Whether from arrogance or incompetence, Mark Zuckerberg has a tendency to issue statements about his company’s intentions that seem meant as matter-of-fact justifications but come across as confessions of the kinds of damage he is prepared to inflict.

The classic example is his 2010 declaration that “having two identities for yourself is an example of a lack of integrity,” meant to justify Facebook’s “real names” policies and the overarching strategy of data collection as a means of integrating information about users to make them into marketing targets. That statement is obviously not factual, but it did reveal a lot about the company’s aspirations then to be the arbiter of “integrity” across a range of social relations. (This was the era when people were urged to treat someone not having a Facebook account as a mark that they were suspicious, that they had something to hide or were pathologically antisocial.)

Zuckerberg has also made countless preposterous statements about the “metaverse,” the now sidelined initiative to force everyone to live more of their lives under corporate surveillance in environments under complete corporate control. “Think about how many physical things you have today that could just be holograms in the future,” he mused in a “Founder’s Letter” from 2021, as if the tangibility of the things that belong to us was a long-borne and widely detested onus. Behind this transparently stupid statement was the obvious aim of the then newly christened Meta to stake an ownership claim not only over users’ “true identities” but over all the things that populate their sensoria, replacing physical reality with virtual realities for which we would need a cascading array of subscriptions to navigate the ever-proliferating levels of differential access.

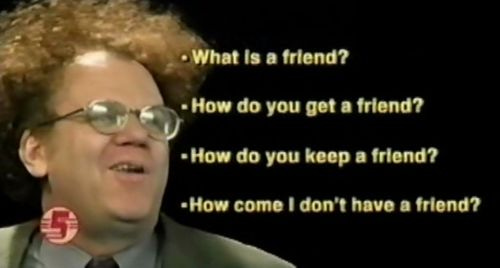

The latest candidate for the canon is Zuckerberg’s claim on a podcast this week (detailed by 404 Media here) that “the average American has, I think, it’s fewer than three friends, and the average person has demand for meaningfully more. I think it's something like 15 friends or something.” He says that “people just don't have as much connection as they want,” and suggests technology can remedy the deficit by simulating it. The aim telegraphed by these inept statements is Meta’s hope to replace human friends with chatbot products under the auspices of combating “the loneliness epidemic.” (Strange how it’s rarely proposed that we address the loneliness epidemic by attacking its root causes: capitalism and technologically driven anomie.)

Many commentators have pointed out that Zuckerberg’s statement sounds like something that someone who has no friends and who is perpetually surrounded by toadies and opportunists would say. It betrays a blinkered understanding of friendship (or “connection,” to use the network-derived term Zuckerberg prefers) as being like a consumer good, something one has a quasi-economic “demand” for in the midst of an uncertain supply, something you should stock your pantry with, something that has an optimal consumption dosage. It seems to posit that having friends (“connections”) is something solitary individuals can elect to choose; they are free presumably to decide how much time and money they should allot to friend acquisition, which is all that limits their total. Likewise, friendship is regarded as something from which satisfaction is extracted on an individual and unilateral basis — you take pleasure in friendship, whether or not it is given.

The idea that reciprocity, responsibility, and care are aspects of friendship is alien to Zuckerberg’s apparent vision of the world, as the trajectory of Facebook as a company has long made plain. His platform has always encouraged users to view friends as resources and as content. Built into the mission of “connecting the world” is a view of people as nodes or sockets into which wires can be plugged or unplugged at the network scientists’ whims, and a view of “connection” as a matter of signal efficiency rather than meaningful exchange. So naturally he would see no concerns in replacing human contact with LLM-generated content—connection is connection, and it doesn’t imply the mutual interpenetration of consciousnesses. You can connect with a person, or a joystick, or a spreadsheet, or an algorithm, and it all counts the same.

It’s no surprise that, as John Herrman explains, “Zuckerberg imagines media platforms in which other people are augmented or replaced by chatbots trained on their collective data, with all parties involved coming together to engage with content produced by AI tools trained on ‘cultural phenomena’ in a space arranged according to opaque and automatic logics.” Herrman points out that this merely extends the premise that one now uses Meta platforms not to engage in friendship but to communicate with algorithmic systems to guide the kinds of entertainment content they supply. Talking to a bot is just a new UI for the long-established slop machine.

So why does Zuckerberg talk about “friends” at all? Is there some dim awareness that people don’t want too clear of a look in the mirror Meta supposedly holds up to them, and that they still need to be coddled with promises of camaraderie to distract them from the slurry they are killing time with? Is the idea that if you call TV shows something like Friends, the viewers feel less guilty and less emotionally stunted when consuming them?

I argued before that “social media” was an alibi for injecting more TV into people’s lives to take advantage of increased network connectivity — that we had to be persuaded that it was a pro-social thing to do to carry little TVs around and watch them at every possible moment. Conflating friendship and entertainment was part of that campaign. Now chatbots are being put to work on the same ideological project: Here are entertainment products that you can treat as friends, just as you have become accustomed to regarding your friends as entertainment products.

But that Zuckerberg and other tech moguls have to go on podcasts and make idiotic pronouncements suggests that entertainment and friendship are not so easily conflated, and that inculcating that ideology requires constant hammering, constant bolstering not only through apps and interfaces but from media coverage that is meant to normalize what we all tend to resist, the idea that we should use other people for our amusement and nothing more.

I’m always perplexed by the idea that anyone would want to have small talk with a chatbot, could find what a chatbot has to say intrinsically interesting simply because the chatbot said it. It’s common to have such conversations with people, where the point of talking is not always to communicate information but also to establish a bond, to indicate that you are willing to pay attention to each other, that there is a fulfilled expectation of mutual care. But chatbots don’t care about you any more than Meta or Google or OpenAI does.

Similarly, a lot of the information I receive from other people is meaningful to me not in itself but because they chose to share it. There is some of that “desiring the desire of the other” that Kojève writes about to it; I want to care about what other people care about because they are people, not because the object of their care might have some utility for me alone. The information we exchange is sometimes no more than a token in strengthening or articulating a relationship among people willing to be with one another. But getting information from a machine offers none of that. There is no desire behind what it generates, or if there is, it is infinitesimally extenuated and impossible to ascribe to human care.

I get this feeling from algorithmic recommendation: Even when it is “correct,” it feels empty, utterly meaningless in comparison with being told by a friend to check something out. It is as hollow to be told what a machine wants for you as to be told what a machine generated — is there anything worse than someone prefacing a statement with “I asked Chat-GPT and …”?

But maybe there is a dialectic to algorithmic recommendation that makes moments of reciprocity resonate even more powerfully. The more the world fills with slop, the more human gestures stand out and reverberate with new meaning. Accessing glib simulations of information will have become commoditized, but someone actually telling you something, anything, will seem more important than ever.

loved the penultimate paragraph in particular. thanks.

What you write about "a lot of the information I receive from other people is meaningful to me not in itself but because they chose to share it" really resonates. I also feel that hollowness--and a flattening. While actual relationships create expansiveness in what you talk about and learn, algorithms and LLMS are narrowing in giving you what you want to see and hear. This post makes me extra grateful for those rambling, wandering interactions with people I love