Methexis in darkness

As a longtime philistine, I have always been attracted to Pierre Bourdieu's Distinction. His ideas there seemed to me to demystify the ideology of aesthetics, presenting taste as an expression of class status and power, with the relation to "beauty" or "the good" serving only as an alibi. On this view, the objects of taste are intrinsically worthless and gain meaning only in relation to other objects, functioning together like a clumsy language that can express only hierarchical gradations. "Art and cultural consumption are predisposed, consciously and deliberately or not, to fulfill a social function of legitimating social differences, Bourdieu claims in the introduction to Distinction. One is bestowed a seemingly natural competency in speaking this language — one's "habitus" — but this is equally an acquisition and a forgetting; one comes to experience one's own taste as natural even as one learns how to deploy it as a form of "cultural capital" to try to win symbolic forms of profit.

When I first came across these ideas, I found them liberating. They suggested that my anxiety about having bad taste was structurally ingrained, not a personal or moral deficiency. I could stop worrying about trying to play a game I was born to lose. I could also stop worrying about having "aesthetic experiences," because from this perspective, there aren't any, nor any privileged works that could inspire them. Anything that is used to speak the language of status becomes as significant as anything else, so on this plane the Kreutzer Sonata is no different from an Eagles game. At the same time, there is no specifically aesthetic form of pleasure, just the enjoyment of domination or of being dominated, filtered through the manipulation of various totems. To a vulgar Bourdieusianism, any pleasure one takes from listening to music, say, is ultimately reducible to a sense of superiority over others; the specific tones and harmonies and whatever are just elaborate pretenses that serve to make the different status positions plain to those with the wherewithal to decode them. Claiming to like anything is just a tactical move.

In seeming to allow me to see through the whole charade of taste, this sort of thinking seemed to somehow make me feel exempt to the theory's implications. It was though I could stand outside the game of taste and open up a new private space again for aesthetic experience for myself that didn't derive from or depend on what other people think. But in fact, the pleasure in this experience of knowingness is precisely the sort of thing Bourdieu is talking about. Being able to deploy a Bourdieu-based lens is itself a kind of cultural capital, a covert assertion of status whose pleasures stem even more directly from undermining the security of other people's cultural position. You think you like music, but you just love power.

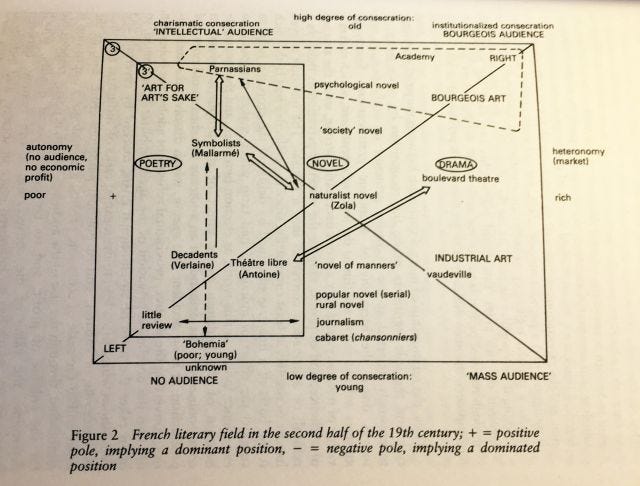

Nevertheless, it feels sort of claustrophobic and hopeless to attribute everything to status seeking, and to posit the scramble for recognition and respect as an inevitable zero-sum game. It's a way of pre-emptively and reductively assuming the worst, shutting off aesthetic possibilities that don't hinge on individual striving. In this recent New York Times piece, Michelle Goldberg cites a Bourdieu-esque line of thought from a forthcoming book by W. David Marx, who argues that "status struggles fuel cultural creativity in three important realms: competition between socioeconomic classes, the formation of subcultures and countercultures, and artists’ internecine battles." When such struggles grow slack, culture allegedly becomes "boring," because no one is sufficiently incentivized by power and glory to make interesting art. This is apparently the internet's fault for "debasing" the value of cultural capital and the high art associated with it (what Bourdieu calls "the field of restricted production"). So, according to W. David Marx, this makes "popularity and economic capital even more central in marking status” and leaves “less incentive for individuals to both create and celebrate culture with high symbolic complexity.”

I disagree with almost all the presuppositions built into that argument: that "individuals" make culture, that culture is now "boring," that people no longer develop or consume "complex" art, that cultural capital has been diluted by broader access to cultural goods, that wealth and popularity confer more status now than they have in the past, and so on. It points to the limitations of the underlying premise that status motivates everything, a claim which seems less a part of a demystifying and materialist analysis of culture than an ideologically motivated attack on any other possible motives for behavior that would threaten to denaturalize competition and the value of demoralizing people.

Goldberg claims that "in the age of the internet, taste tells you less about a person. You don’t need to make your way into any social world to develop a familiarity with [John] Cage — or, for that matter, with underground hip-hop, weird performance art, or rare sneakers." Not only does that claim seem preposterous (taste is mobilized and metricized everywhere on social platforms) but it also assumes that the internet isn't itself made up of "social worlds." The information one accesses online isn't simply there; it's organized and sustained socially, even if individuals may access it through a solipsizing interface.

Goldberg's claim also conflates being "familiar" with cult objects with a knowledge of them that others will find convincing. But mere familiarity tends to underscore a person's lack of authoritative understanding — it shows up the misalignments of their habitus, their inability to turn familiarity into authority. Familiarity doesn't make you a priest in the cult, and it certainly doesn't devalue the priests' cultural capital. Rather, as Ryan Broderick points out, widespread access to cultural goods further attenuates the requisite knowledge to seem authoritative, what he calls "the lore." He argues:

In a world where you can read, watch, or listen to anything, the act of consumption isn’t impressive. So now we reward each other for consuming the meta-text — the memes, the hashtags, the community drama, and the conspiracy theories.

But again, the act of consumption alone was never any more impressive than sheer familiarity: The main point of Bourdieu's theory of habitus is that there are right and wrong ways to consume things that confer status distinction. Broderick suggests that the "link between status and culture is gone" and that the internet has "replaced all of it with a link between status and fandom," as if an interest in refined detail were an innovation devised by fan culture. That is just how distinction has always worked. More plausible is the possibility that the internet has facilitated the growth of fan culture to absorb more people into a mode of consumption that is fixated on status and hierarchy rather than other (aesthetic) possibilities. One could even argue that obsessional fandom is not any more impressive to outsiders now then it ever has been, despite being more popular and economically lucrative, and that its pervasiveness thereby augments the cultural capital of not being a fan, a comportment that now seems even more rarefied.

Fan culture used to be associated with a utopian vision of bottom-up collective participation and an egalitarian leveling of cultural authority; now it tends to be associated with ressentiment, endless squabbling, and quasi-fascist mobilization.

Strangely, I find this chart from Fredric Jameson's Late Marxism to actually be helpful in thinking about that shift. The chart attempts to schematize Jameson's reading of Adorno's aesthetic theory into a set of related oppositions that map possibilities for art and its related audiences. There is "real art" in the top left, the great art that elicits an ineluctable aesthetic response in those who can hear it. Opposed to that in one sense, in the bottom left, are those who can't respond to art at all, who like Odysseus's oarsman have their ears stopped up to the sirens' song.

Opposed in a different sense is "false art" manufactured in top-down fashion by the culture industry to mechanistically manipulate and control the masses, or as Jameson puts it, "a passive public submits to forms of commodification and commercially produced culture whose self-identifications it endorses and interiorizes as 'distraction' or 'entertainment.'" That view of passive reception is precisely what the utopian ideas about fan culture were developed to opposed, which suggests what belongs on the chart in the "?" spot, as part of the concept that negates the understanding of audiences as passive.

But the point of the chart, as I understand it, is to illustrate that an audience can be active while remaining "art-alien," rejecting an aesthetic comportment toward experience. Jameson labels this group as "philistines," and I suppose I feel seen. "Philistines," Jameson writes, are not

in Adorno's scheme of things, those who passively consume mass culture, nor are they the oarsmen, who are deprived of the very sense organs for any culture, whether authentic or commercial, but rather those who carry in their hearts some deeper hatred of art itself.

Their "gesture of refusal" stems not from an inability to respond to art but from a resentful sense of social exclusion from art's (always broken) "promise of happiness" that is irreducible to domination (or really anything that can be discursively expressed). In a striking and characteristically obscure passage from Aesthetic Theory, Adorno declares that

the tenebrous has become the plenipotentiary of that Utopia. But because for art, Utopia—the yet-to-exist—is draped in black, it remains in all its mediations recollection; recollection of the possible in opposition to the actual that suppresses it; it is the imaginary reparation of the catastrophe of world history; it is freedom, which under the spell of necessity did not—and may not ever—come to pass.

For Jameson, philistines can't believe in that promise and mobilize their energies to a different sort of project, the direct formation of (fan) communities in which to express in more or less oblique ways the inevitable resentments they feel at coming up against the reality of class society, the existence of habitus, the commercial to status-seeking motivations of all culture under capitalism, the universal bad faith and cynicism that is seemingly just beneath the surface of everything. If the internet is to be held responsible for this, it would be because it provides fresh evidence of that cynicism at every refresh of a feed.