Might as well go for a soda

Sorry for the extended absence, but I have been on a road trip for the past few weeks through the Maritime Provinces. Heard on Canadian radio: Triumph, Honeymoon Suite, Chilliwack, Trooper, Sloan, April Wine, Kim Mitchell, Our Lady Peace, The Stampeders, Barenaked Ladies, Glass Tiger (and lots of Tragically Hip of course). I was disappointed not to hear any Saga or Red Rider or Helix. Perhaps we didn’t drive far enough, though we did end up in Yarmouth, Nova Scotia, which bills itself as being “on the edge of everywhere.”

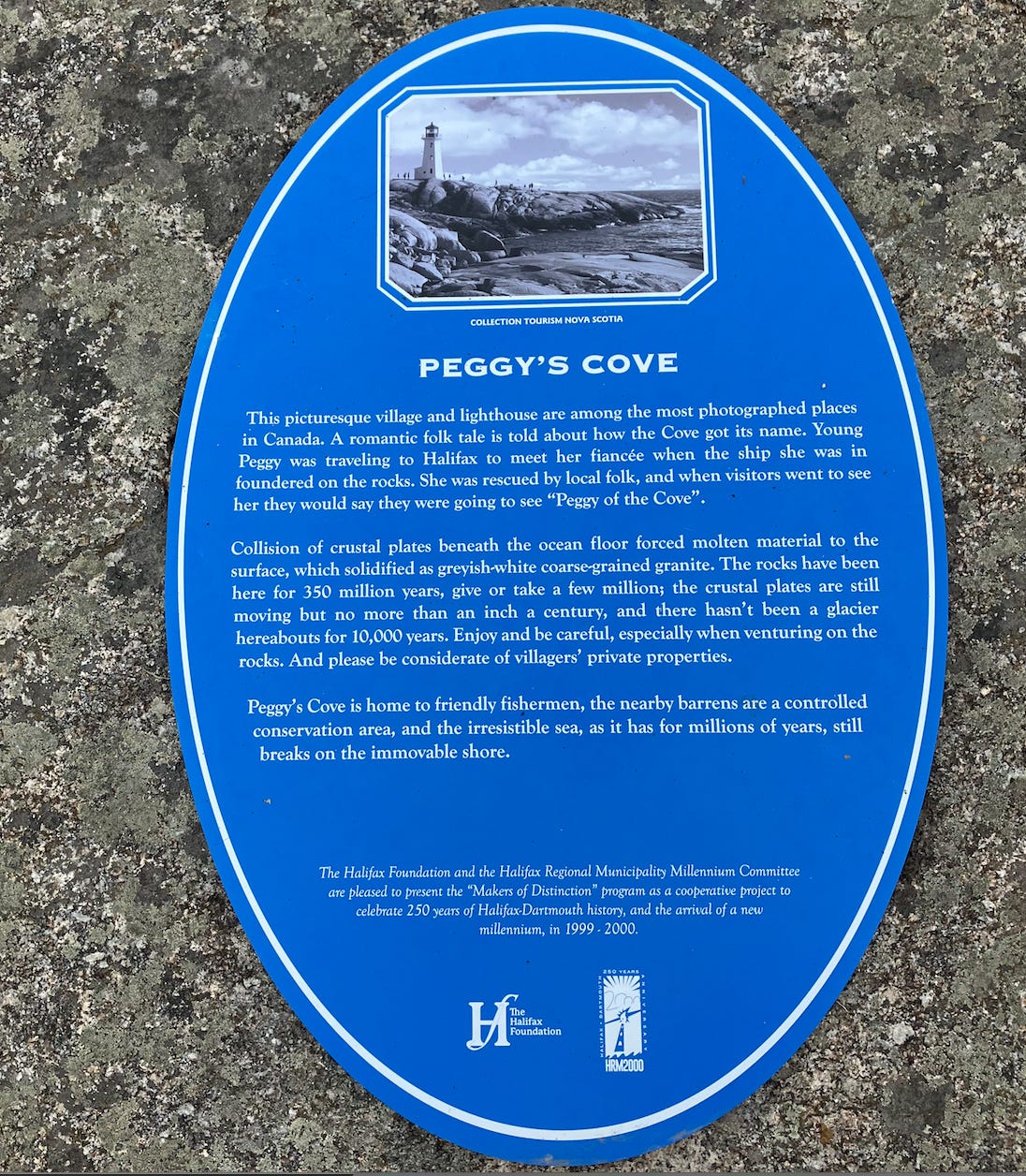

Another of the places we visited was Peggy’s Cove (above, in photo and AI versions), a place I thought was mainly famous for being famous. It’s often touted as featuring the most photographed lighthouse in Canada, so I expected it to be the Canadian equivalent of the most photographed barn in America in Don DeLillo’s White Noise. (Please forgive me for writing about that yet again.) Indeed, a marker in the parking lot outside the village proudly proclaimed the cove to be “among the most photographed places in Canada,” including a photograph of it as if to prove its point.

“No one sees the cove.”

“We're not here to capture an image, we're here to maintain one. Every photograph reinforces the aura.” AI’s processing of troves of social media images has made that literally true in a way; it manifests one version of the “collective perception” that the character in White Noise describes, but it also empties that perception of its “accumulation of nameless energies.”

Generative AI models offer collective perception without any sense of collective participation; they generate not “pictures of taking pictures” but the idea of pictures without picture takers, fully demystified images with no aura at all, severed from anyone’s ritualistic touristic practice and evincing no “spiritual surrender,” just tech companies’ megalomaniacal ambition to replace human experience with the synthetic products of their appropriated and now proprietary data hoards.

The depressing existence of generative AI, and of people intent on promoting it as a viable replacement for human endeavor, sometimes overwhelms me. I look at the output of text-to-image models and regard them as unstoppable engines of trivialization, rendering mediocre versions of anything anyone might want to see and perhaps curing them of their outmoded curiosity. But that is only one side of the dialectic. The banality of synthetic media seems capable of re-enchanting even the most mundane of our attempts at documentation and creativity, with the obscurity of black-boxed statistical processes of machinic creation paling before the unresolvable mysteries of ordinary human intentionality.

At Vox, Rebecca Jennings suggested that in the wake of “internet-driven over-tourism,” such tourism may have somehow become newly “cringe,” as if it weren’t already. “In catering to Western tastes,” Jennings writes, “developers and the dollars they seek aren’t only killing the existing culture, they’re also, ironically, killing what makes people want to visit a place.”

Whether that is “cringe” perhaps depends on how you interpret the word. If “cringe” means “passé” or “basic” — if it is being pronounced from the perspective of the influencer who needs new create fresh content and subordinate places to their personality and brand — than one could conclude that there is some danger of a city being overexposed, played out. (Is it not “cringe” to be the shock troops for capitalism, discovering underexploited places that can then be assimilated to the value-extracting system?)

I tend to understand “cringe” more as an expression of steamroller privilege, an imperviousness to embarrassment, and I suspect many tourists travel precisely to inhabit that Mr. Magoo-ish subject position, with an entire industry to cater to your whimsical myopia. Expanding that industrial capacity to accommodate tourists in their self-importance likely makes sites more rather than less popular, much like adding lanes to a highway makes it more congested. People may bellyache about how crowded and inauthentic it all is, but that is also part of their enjoyment. Living in New York City has fully convinced me that there is nothing tourists are more eager to do than to wait in lines. Crowds are an amenity.

Much anti-tourist discourse revolves around an longstanding opposition between tourism (the terrible, routinized thing they do) and travel (the endlessly surprising journey of discovery I have embarked upon). This opposition seems to govern Jennings’s conclusion, that with respect to tourism

what’s embarrassing, then, is the obsession with getting everything right, with the spreadsheets and the research and the taking of the thousandth photo, followed by the pouting because the bar was too crowded or the emotional unleashing on a service worker because your train got canceled due to a railway labor strike. You are not a good or more interesting person because you have visited 35 countries before the age of 35, or because you’ve dined at every restaurant on Bon Appetit’s guide to Tokyo’s best izakayas. The quality of your photos does not equal the amount of fun you had on a trip.

Throw away your Baedeker and experience the authenticity that comes with unscheduled spontaneity! Life is not checking items off a list; it’s having serendipitous encounters that disclose the true essence of different ways of being!

But the pursuit of authenticity is an equally good way to ruin a vacation. Second-guessing whether what you are doing is too touristic is just another expression of the “obsession with getting everything right.” Not photographing the picturesque place is just as contrived as taking multiple shots of it. Trying hard to blend in as a local is just as preposterous as being loud or demanding, or going to see only the well-promoted sights. Demanding serendipity is self-canceling.

One might be trained by anti-touristic discourse to expect from “destinations” nothing more than what it turns out that AI can provide of them — inert average renditions, pre-digested. Generative AI is predicated on recursiveness, on the diminishing returns of overfamiliarity, on the premise that words and images are ultimately just commensurate forms of data, just information that adjusts the probabilities of what should be happening from a statistical perspective. It has the eyes of the stereotypical tourist; it sees the world as a big long checklist of material to systematically absorb.

Yet I am becoming more hopeful that the more exposure one has to generative AI — particularly as it fills up search engines and platforms and makes them even more stale and frustrating — the more refractory one’s actual experience of the world will become, even in the most reified of occasions. The story behind the most cliched tourist photo has more intrinsic interest, more of a story behind it, than any generative image. Lots of people, including me, photographed the lighthouse at Peggy’s Cove, but that’s because the real attraction of the place is essentially unphotographable. People take pictures of the lighthouse, but then they clamber through the fog over the rocks and find different places to stare out across the waves. As the copywriter of the parking lot placard avers, “the irresistible sea, as it has for millions of years, still breaks on the immovable shore.”

While traveling, I also noticed that Twitter had made the old version of TweetDeck inoperable, which effectively ended my willingness to use Twitter in any capacity and even prompted me to beg for a Bluesky invite. But when I got home and checked again, the old TweetDeck had been reinstated and it was business as usual again. If anything, the much-trumpeted launch of Facebook’s Threads app (wow, so many downloads, so many celebrities and brands, so impressive!) has made Twitter seem comparatively good and necessary again. Despite myself, I found myself mostly agreeing with this contrarian take that “Twitter is better than ever,” if only because the broader social media climate is worse. If 90% of the Twitter experience is garbage, that for me is still better than the algorithmically driven 100% trash of Instagram and TikTok. I can still follow the people I want to follow on Twitter, and they haven’t stopped posting. I get links, some jokes, some commentary, and a sense of “the discourse” that doesn’t seem out of control, as long as my lists and blocked words are intact. None of my (half-hearted) attempts to find similar utility on any of the other Twitter-like platforms have yielded encouraging results.

Instagram CEO Adam Mosseri claimed that the purpose of Threads is “to create a public square for communities on Instagram that never really embraced Twitter and for communities on Twitter (and other platforms) that are interested in a less angry place for conversations, but not all of Twitter.” Though that statement was probably disingenuous, it still seems strange to me — even after having spent the past two weeks as a tourist — that anyone would think the world needs more spaces where people can be inundated with contrived fun and phony positivity.

Leading the cheerleading, the New York Times reported a few weeks ago that “celebrities, brands and influencers were given early access to the app over the past few days, a move by Meta to kick-start a freewheeling culture of fun and discussion.” Who doesn’t love the bracing discussions led by celebrities and brands? Who’s more spontaneous and “freewheeling” than influencers?

Rather than provide a rival to Twitter, a place where news happens and information (for better and worse) is live, both in the sense that is in real time and in the sense that it is living, effectual, occasionally capable of moving in noncommercial directions, Facebook decided, at a moment when Elon Musk’s blundering has left many Twitter users searching for an alternative, to cater to people who don’t want what Twitter does and have already rejected its format. No matter how many millions of Instagram users inadvertently sign up for Threads (I’d have assumed it was a Temu or Shein clone before I would have landed on Twitter), it will still fail to have any cultural impact because it is already entirely redundant by design.

Ryan Broderick pointed out that Threads has “more or less has the exact same social graph as Instagram. Why would users put up with a rate limited, text-heavy version of an app they’re already using?” Previously he had declared that “Threads sucks shit. It has no purpose. It is for no one. It launched as a content graveyard and will assuredly only become more of one over time.” That sounds about right. I can’t decide, though, if that makes it more or less like the most photographed barn in America.

One theory about Musk’s acquisition of Twitter, which Broderick partly sketches out, is that it allowed a billionaire to singlehandedly neutralize a site where oppositional discourse could still gain traction, where insurgent movements could gather momentum and the oppressed could speak truth to power and extract accountability from otherwise indifferent institutions. At the same time, Musk could amplify the demagoguery and divisiveness that has traditionally splintered the oppressed classes and make the site function like conservative talk radio or local TV news broadcasts.

Facebook and TikTok approach the same goal from the opposite direction. They don’t aspire to produce and administer divisiveness as spectacle; they instead produce a false unity of populations equally and algorithmically stupefied on an individualized basis by entertainment programming. Both these approaches aim to render “the masses” as politically inert and easily controlled; both make the participatory aspects of social media into de facto forms of self-depoliticization, akin to what Marcuse described as “repressive desublimation.” (As he cheerfully puts it, “Pleasure generates submission.”)

Generative AI may prove to be the most comprehensive strategy for neutralizing whatever potential that social media has left for sustaining forms of resistance (if it ever had any, on balance). If it is not heaven-banning users in a chat interface, then it is serving as a means for every available communication channel to be filled with content that has no other purpose than to discredit the idea that anything could ever be anything other than content. “The metaphysics of the code,” as Baudrillard called it.

In Symbolic Exchange and Death, he writes:

We pass from injunction to disjunction through the code, from the ultimatum to solicitation, from obligatory passivity to models constructed from the outset on the basis of the subject’s ‘active response’, and this subject’s involvement and ‘ludic’ participation, toward a total environment model made up of incessant spontaneous responses, joyous feedback and irradiated contacts.

That still strikes me as an apt description of commercial media platforms, but an even better description of how their purposes have been perfected by generative AI, through which everyone is treated as training data.

Maybe the pictures we take for ourselves will allow us to disprove that, and maybe samizdat networks will spring up again in which humans will be able to recognize one another, perceive in each other motives that diverge from the predictive diktats of AI models, not to mention the programmatic incentives of competing for attention in algorithmically governed feeds. But the authorized media channels will be filled with infinite television, simulations of simulations of simulations.