Practico-inertia

Google recently released an generative model called Gemini but had to suspend its image-generation capabilities because of how it was programmed to address brand safety concerns. In part because of how the model would rework users’ prompts after they were submitted, it produced what the company conceded were “inaccuracies in some historical image generation depictions.” (It generated images of nonwhite people when they weren’t requested or apparently expected.)

As the company’s convoluted description suggests, the epistemological status of these images can be a bit hard to articulate. They are “depictions” of “historical images,” or of “historical image generations,” because they are not historical at all. They have “inaccuracies,” but inaccurate with respect to what, and on what basis? Can generated images even be accurate or inaccurate? As Chris Gilliard asks in this piece for the Atlantic, “Is there a right way for Google’s generative AI to create fake images of Nazis?” Or as Max Read asks here, “What are AI chatbots for?”

Some people seem to want to think (pretend?) that generative models produce knowledge, that their stochastic parroting should be understood as a valid and objective representation of reality. At the same time, they think models can supersede the human imagination to represent the otherwise unimaginable and purely subjective. As Read puts it: “Is Gemini a program for obtaining true or accurate information? Is it for making text or images to any parameter the user desires?” He quotes John Herrman, who points out that generative models are understood as both “documentary and creative,” a combination that can’t be made to cohere in any conventional epistemology. The seemingly contradictory expectations — Read calls them “mutually exclusive” — add up to the fantasy that generative models can make truths we can’t otherwise imagine, pseudo-empirical representations that are both objective and beyond confirmation at the same time.

Another way to resolve the contradiction is to treat a model’s output as bespoke truth: The prompter is given a powerful machine to manifest the world they want to see and believe in and take for their own personal reality. From this assumption follows the idea that generative models will lend support to a VR-helmeted future in which no one wants or needs to share the same ground truths, as well as the benighted prediction that the future of entertainment will be in completely individualized content, a kind of benevolent Truman Show delusion for everyone.

I don’t think people care that much about things only they can see. I don’t think aspirational solipsism is all that common, no matter how well refined the sales pitch for its “convenience” may be. Much of the pleasure of “generating content” — whether through a machine or by some other means, about oneself or about other things or about other things as a way to signify oneself — is in imagining that someone else might also want it. The content is not just for you to consume but to anchor shared experience, or at least allow us to imagine its possibility. Content implies some eventual negotiation of intersubjectivity at some point, and even generative models, which can’t negotiate any kind of subjectivity whatsoever, still produce content that serves that function once humans see it.

The people complaining about Gemini’s “woke” depictions of various verbal constructions clearly accept that. They reacted as though there were self-evident social stakes in the images they were prompting for and sharing, and as if Google were forcing them to pay attention to a reality they didn’t want to see (even though they were voluntarily asking a machine to invent it). That is, they understand the purpose of chatbots and generative models to be the ability to force other people to see a particular version of reality. It is a tool of power that masquerades as a tool of knowledge.

As Read suggests, it seems pretty silly to ask a language model to rate Hitler. “Imagine getting so mad at your computer because it won’t say whether Elon Musk or Hitler is worse that you insist that the head of the computer company needs to step down! I mean, imagine asking your computer in the first place if Elon Musk or Hitler is worse!” Of course it is childish to expect “right answers” to those kind of questions. But these are the awkward postures one must assume not only to posit LLMs as a potentially lucrative product (as has been widely pointed out) but also to sustain fantasies about there being a perspective that certain special people have a right to claim as neutral and objective, despite the intrinsic and inevitable biases of any situated knowledge.

If you are willing to construe generative models as knowledge producers, as truth-tellers, despite the obvious leaps of illogic it requires to think that, it must be because you really want to believe in the power to indoctrinate. You have be upset when they “fail” so you can pretend that they can succeed. You have to act like models make facts because you expect or crave the ability to force a “reality” on others, to make them adhere to your norms. The Gemini complainers must have thought that they would of course control the truth-imposing machine and were panicked to suddenly find themselves ambushed by ideology.

That Gemini’s release could become a fiasco is the fiasco: Generative models should not be invested with the capability to arbitrate reality, and any discussion that forwards that idea shifts more power to the companies that amass the data and build the models. The only knowledge that models produce is about the composition of their training data and the methods they use to process and organize it. Those methods don’t reflect anything about how the world itself works.

Rather than debate the status of generative model’s outputs, perhaps more attention could be paid to the status of prompting: what does it mean to “prompt” when the prompts are recast in opaque ways that suit the company’s ends. This is a variation on the question of what it means to query a search engine when it interprets the query in obscure and self-serving ways. There is a tendency to see prompting as something an autonomous user controls completely, only to be thwarted afterward by some sort of censoring guard-rail process — as if a prompt had a natural response that should be expected in pure conditions, as if the model itself were a natural process and not something designed. But users have no control over their prompts; they have curtailed their autonomy once they decide to use a model (or a search engine). That we can write the prompt or query is not an emblem of our freedom but of our surrender. We give up on what we think the words mean and let the machine process them in alien and opaque ways.

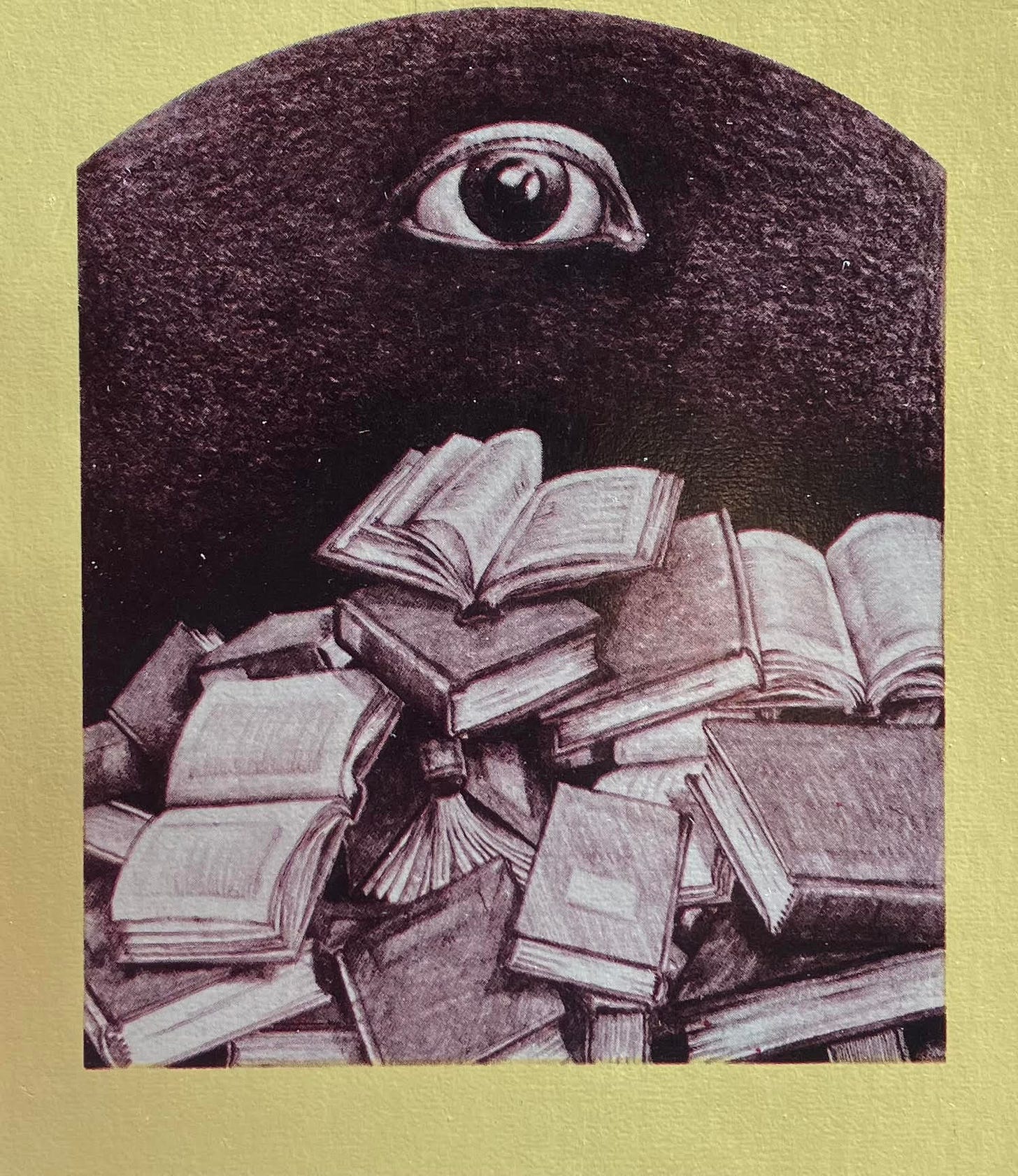

If language is the medium of our intersubjectivity, each LLM prompt signals an attempt to withdraw from it, to stop negotiating the meanings of words and things with others in order to lapse into a kind of docility where words have become an instrumental, transparent code that can program us. Prompting is a way of letting go of language, a way of admitting that we are no longer willing or able to conceive of what those words mean.

Your lucidity on LLMs/Generative models has been a very welcome dose of solid ground amid the endless hype. Thanks for writing these past few posts.

Brilliant.