Some people never know

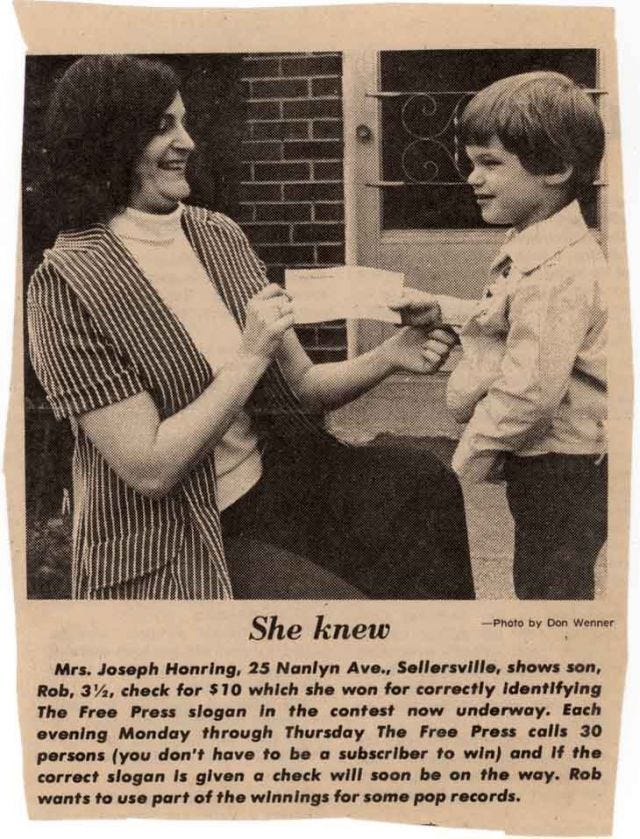

The earliest photo I have of myself is this newspaper clipping above, from 1974. I have no memory of this event happening, and I am amazed that it exists for many reasons, not least that it forms a hieroglyph of my entire adult personality. Win a random contest, have your name spelled wrong, buy some pop records: I have been operating within these horizons for as long as I can remember.

If any records were actually purchased with the winnings, they would undoubtedly have been by Paul McCartney — maybe "Junior's Farm," which came out that year and which I definitely had in my 45 collection. Or maybe "Uncle Albert/Admiral Halsey," a 45 I remember playing a lot on my toy record player. Actually almost all of my earliest memories of childhood involve listening to Beatles and Wings records, making me a lifelong fan of Paul McCartney in a very literal way. I don't remember discovering his music or being introduced to it. It was just there, a priori. In a sense Paul McCartney was in my head before I was.

Lately I have been listening to a few Wings records in particular: Wild Life and Red Rose Speedway, ones I didn't get as a child and have only come to appreciate recently. For a long time, I thought of Wild Life especially as more of an ego-trip gesture than an album, half-written songs released just to show that he could get away with it, much like he could record "Mary Had a Little Lamb" and release it as a single. I saw it as a failed repetition of the approach taken on his first solo album, a home-recorded collection of scraps, fragments, and leftovers that seemed designed to underwhelm — or more precisely, to give the impression that he can be interesting without even trying. It's not quite as contrarian as something like Bob Dylan's Self-Portrait (which I've also written about), but it seems to pre-emptively court disappointment.

After all, McCartney was coming off of spending the past few years being among the most famous people alive and was writing songs like "Let It Be" and "Hey Jude," which were taken as ecumenical hymns for the masses. The songs on McCartney were not anthems of world peace or the triumph of the human spirit; they were hardly even songs at all. The album was more a declaration that the McCartney of "Wild Honey Pie" and "Why Don't We Do It in the Road" was now at liberty to do his thing. As he wrote in the press release he put out to accompany the album (after claiming that some of its songs were recorded "to test the equipment"): "I will continue to do what I want — when I want to."

Wild Life seems very much in that spirit. In 1971, people were probably going to hate any band with Paul McCartney in it that wasn't the Beatles; Wild Life takes that into account and leans into it. It's often described as a demo for the formation of Wings, and it introduces them in what must have seemed to be the worst possible light. It begins inauspiciously, with the sound of a tape machine coming up to speed in the middle of a song, as if the engineer made an accident in editing it down from a longer jam session. (Maybe it was conceived in part as an answer to the awful "Apple Jam" disc of George Harrison's All Things Must Pass.) This song is the suitably named "Mumbo," whose gibberish lyrics seem made up on the spot. It's followed up with "Bip Bop," another song with improvised nonsense lyrics that McCartney would later describe as his worst song ever. Another song in the same vein, "Hey Diddle," didn't make the album, but this video clip seems to me to encapsulate the vibe McCartney was then going for, relaxing in a meadow with his family (including his sheepdog) and reeling off melodies as though they were casual conversation.

The album concludes with a mournful dirge directed at John Lennon, "Dear Friend," but the album cover — almost a parody of Lennon's Plastic Ono Band — seems a more pointed message. Where Lennon was getting back to his roots by getting psychoanalyzed and writing "raw" songs about his childhood and his Beatles experience, McCartney was singing nursery rhymes and hanging out with his new band. He was getting back to roots in his own way, at the level of form rather than content.

I used to listen to Wild Life and Red Rose Speedway and think that McCartney had just run out of ideas as a lyricist at that point. Songs like "Big Barn Bed" seem like they have placeholder lyrics that never got replaced — as though he wanted to put out "Yesterday" as "Scrambled Eggs." It seemed lazy to me then. Now I interpret it differently. I imagine that it's not that McCartney couldn't come up with words, but that he was aware at some level that any coherent lyric would automatically come across as though he was trying too hard. His fame made him a walking platitude; everything he would do was fated to become instantly overfamiliar, obvious somehow even when it was original.

In more recent interviews, McCartney tends to stress how the early Wings albums expressed the desire to do something new, to escape the shadow of the Beatles, even if that meant putting out half-baked tracks. So much of rock music was derived from the Beatles, inspired by it, that he may have felt he had no other way to avoid sounding like himself, to assert his unpredictability as more fundamental. He had spent years making the biggest pop records ever made and had become intimate with how his self-satisfying ideas turned into massive commercial entities with public lives of their own. If he was going to do something different, he had to resist that moment of polish that began to shape the moment of musical inspiration into a commodity. He had to try not to try.

So the songs on his first few solo albums tend to be embryonic, as though he is hoping to capture just the inspiration, just the fragment, just the hint of melody that made him think he had something, and freeze it there — like many songwriters he claims the music comes to him from somewhere else, that it is not a matter of direct will but a kind of channeling. With these fragments, it's like he is trying to get at the channel itself, trying to recover the core of why he is capable of making music at all, and the only way he can feel it for himself is if it threatens to alienate everyone else, if it offers them no words to let them in.

This approach reaches a pinnacle with the medley of songs that ends Red Rose Speedway, which calls back to Abbey Road's side-two suite but is even more conceptually slapdash. For me it's among purest pieces of McCartney there is — the effortlessness of his melodic gifts finds a belabored form that is somehow perfectly appropriate to it, fusing the contradictions. It is ambitious and incoherent, palpably purposeless ("purposive without purpose," as Kant defines the beautiful). It sounds like likability without ceasing to be fundamentally inscrutable. It doesn't add up to anything, but I never stop trying to make the calculations.

***

There seems to be a formula for writing about GPT-3, the Open AI language-prediction model that can be used to generate convincing-sounding text from a prompt: The writer will reproduce some stories GPT-3 has composed and invite readers to marvel at how human-like they are. Some rote comments will follow on how that's both scary and amazing, and then a shrug: Oh well, this technology exists now, so we must all accept it in all its far-reaching implications.

Rarely will there be much speculation on what sort of return its funders expect from it, the resources required to maintain it, or what kinds of epistemological biases are built in to how machine-learning systems and "neural nets" are designed — how these will become productive of the sort of reality they assume when they are reproduced and implemented at scale. Instead, we are implicitly persuaded to wonder at the apparent intentionality in the machine's output, and not in the use to which that output is being put, let alone the machine's construction itself.

This OneZero piece about GPT-3 by Thomas Smith is fairly typical: It outlines in vague terms how it works, adds some caveats about its potential for bias, and then by and large celebrates how "powerful" it is. "Deep learning" techniques applied to "nearly all the public text created by humanity" has made an AI that's basically capable of answering any question about anything in anyway we desire, and its "black box" of parameters and weights means that it can surprise us with the ingenious connections it makes.

Smith characterizes GPT-3 as a "communication tool," but that seems misleading and euphemistic. By his own description it seems more like a search engine; it responds to prompts with chunks of text algorithmically drawn from an archive of published material. But it could also be understood as a technique for producing text without communication — GPT-3 issues compositions without having a rhetoric, a purpose. Or rather, it draws on and distorts past communications, rendering the original, situated intention illegible.

Unfathomable social energies and layers of human intentions are embedded within GPT-3 training samples; machine learning proceeds as though those things can be disembedded, emptied out or translated into code. But those energies are not static; they can't be decontextualized without being falsified. Nonetheless, GPT-3 liberates those energies in chaotic and unaccountable ways; it lets users direct that energy without understanding where it comes from. That is a feature, not a bug. Like most other automated systems, GPT-3 will be used to deflect responsibility for what it does from those who use it, from those who fed it the data or the prompts or made it possible for its output to be circulated. Instead there will be lots of chin scratching: What does GPT-3 want?

I like to prompt AI text generators and enjoy trying to read the results as poetry. But that doesn't make the AI into a poet; it's an exercise in self-flattery, where I can praise myself for projecting poetry into it. If I published what it wrote and insisted it was poetry, I would be the poet — and if you read it, you would be trying to discern what I saw in it to want to put it into that context.

While we can marvel at the plausibility of GPT-3's responses, the fact that they are produced without a methodology that can be audited means that they are worthless as knowledge. Its main purpose may be to automate the creation of text that no one wants to write or read, spamming the world with ceaseless commentary on itself while further reifying the sorts of textual associations that have already been made. Eventually a GPT-4 or -5 will be trained on text that will include increasing proportions of texts produced by earlier GPT iterations. The more we come to rely on these systems to prompt us with plausible text, the more we will be trapped within them, sealed in the envelope of the already expressed.

The developers of these kinds of systems often imagine implementing them to perform "autocompletion" tasks — to think what comes next for you so that you will stop thinking for yourself. ("Completion" generally names a fantasy, or death.) Of course you have the option to reject what the system recommends, but in some ways it is too late: You have already had your sense of the possible shaped by a "powerful" system that has digested everything that has ever been said. The more pervasive and comprehensive that system is, the more that rejecting it will mean rejecting what is normal, and refusing to behave as expected. Such systems could also measure your output in terms how often and how far it deviates from the expected output, a kind of play-by-play "win probability" percentage for every step you take. The investment in predictive analytics will succeed in producing a system that discipline us to become more predictable.

If such recommendation systems become common prosthetics, we may be unwilling to think in any other way than through the machine's predictions. It may be that in the future, if a GPT-like system doesn't prescribe something, we won't believe that it is sayable. Its options will constitute a seemingly complete range of possibilities, because there will be no incentive to think beyond them and no memory of what "origination" or "invention" entails as a practice — no sense of plugging in some recording machines and capturing a moment of inspiration to test the equipment. Instead the machines will begin churning out reconfigured moments of certified inspiration from the past in overwhelming quantities until we are numbed into complacency. We might not know that there is any other sort of resource to draw from.

GPT-3 has been trained to make music like Paul McCartney. This example sounds a little like "Kreen-Akore" before turning into something more McCartney II-ish. Here are some AI-generated attempts to cover the Beatles. I think I'd rather listen to "Bip Bop." What sort of broken machine could come up with that?