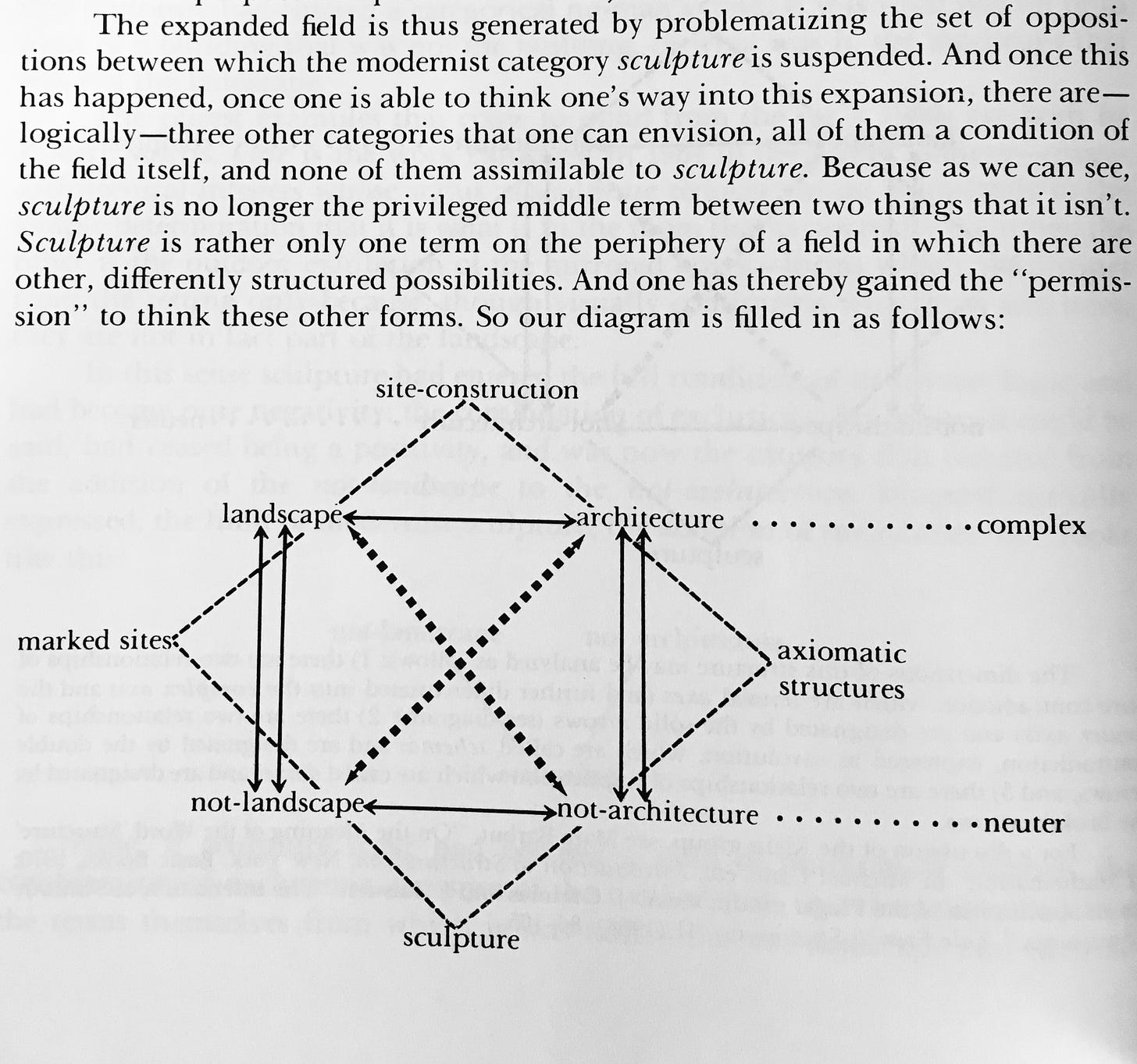

The phrase “in the expanded field” has a satisfying, ready-made memeable quality to it; it seems like it can be added to any given concept to make it sound more interesting: “K-pop in the expanded field.” “Digital feudalism in the expanded field.” “TikTok in the expanded field.” Like chiasmus (“From the Critique of Institutions to an Institution of Critique”), it’s a good gimmick for generating the impression of thought, especially as “in the age of” (“The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” and “the logic of” (Postmodernism, or the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism) have come to feel a bit played out. When I finally got around to reading the 1978 Rosalind Krauss essay that the “expanded field” comes from, I was disappointed that it referred to a Greimas square (above), which seems anything but expansive.

Open AI recently introduced a feature that offers an extremely literal take on expanded field, using algorithmic “AI” techniques to extend images beyond their borders, resulting in extremely corny images like the one below.

Rather than consider the expanded field of Vermeer’s painting in terms of its provenance, the networks it has circulated in, the kinds of knowledge it has validated, the sorts of image economies it participates in, the lines of aesthetic influence that can be traced through it and so on, the Dall-E image simply extends it visually, autocompleting it according to what statistical analysis of 21st century data sets indicate would be likely to be there.

AI images epitomize what Ingrid Hoelzl and Rémi Marie define in Softimage (2015) as “expanded photography”: a photography that is “less bound to a desire for movement (as suggested by realist film history, which presents film as the logical progression of photography) than to a desire for endlessness, a desire for the never-ending view.” This conception of expanded photography derives from images on screens no longer being representations of something external but the results of a specific request to a database — every photograph is a digital rendering rather than a imprint of some physical reality (which implies the world itself can be represented as a database).

One possible implication of this sort of expanded field is that no image should be considered to be finite or framed; they all can be conceived as fragments, no matter how finished or final they may have seemed to be. Any image can be conceived as immersive rather than as a discrete object separate from the viewer — one can expect to navigate beyond the edges of the frame the way one can click around within a Google Street View image. This recasts all images as opportunities for exploration that center the experience of the navigator rather than the intended expression of the image maker.

Of course, when “AI” is the maker, there is no intention there to begin with. AI becomes the means for viewers to overwrite whatever intention there was in framing a particular image in a particular way with their own whimsical desire to reject limits for the sake of it. Images lose their objectivity, in the sense that they offer no resistance to the subject’s willfulness. They serve no representational or documentary or even communicative function; they just convey to the viewer that everything can be molded around them, everything can be reworked according to their choices, their whims, their particular context, their particular history. The extended image has nothing at all to do with Vermeer and everything to do with “prompt engineering.”

As a flat form of virtual reality, immersive images fit Mark Andrejevic’s critique of “framelessness” developed in Automated Media (2019), where he describes it as the other face of ubiquitous surveillance. Putting viewers at the center of whatever experience they have requires that at the same time they are living a “fully monitored and recorded life.” To move beyond the frame means that everything beyond it can already be calculated; it’s all already implicitly inside, already rendered sufficiently and plausibly predictable. “Total information collection and virtual reality go hand-in-hand,” he argues. “Both aspire to the digital reduplication of reality.”

Predictive technologies are rationalizations for surveillance and the control that follows from it, but the fantasies of framelessness work to conceal that — to present control as open-ended possibility. AI image generators present the pre-emptive reduplication of reality as a kind of spurious invention that’s only released by the subject’s desire. They are often described as tools that help subjects unlock their creativity, while containing creativity within the parameters established by datafication. In effect, these tools nullify the idea of creativity (everything is already latent in the machine’s capacity to render visualizations) and drain the potency of desire, which is reduced to mechanistic forms of trial and error. Prompt engineering.

Desecrating works of art along the lines of the “immersive Van Gogh” exhibits and undermining subjectivity as we know it isn’t, however, the proximate purpose of image generation technology. Generally its main use will likely be to complete sketches, flesh out half-cooked ideas, and allow the producers of more humdrum, function-oriented materials — pitch decks, corporate prospectuses, game backgrounds, clickbait articles, and other forms that conventionally require placeholder images — to replace human illustrators and photographers with machines that have inhaled and digested countless examples of their work.

This kind of image squarely falls into Sianne Ngai’s definition of a “gimmick,” as something that appears as “working too little (labor-saving tricks) but also as working too hard (strained efforts to get our attention).” Gimmicks are, she suggests, dissatisfyingly fascinating, like hoaxes. This stems from how a gimmick creates confusion about the value of labor time: “It gives us tantalizing glimpses of a world in which social life will no longer be organized by labor, while indexing one that continuously regenerates the conditions keeping labor’s social necessity in place,” Ngai writes. Accordingly, AI seems as though it can replace labor but in reality depends on hidden, abstracted, and poorly remunerated human work.

Gimmicks are figures for the asymmetries and misrecognitions that capitalism requires to generate profits — the wonderment that attends what are ultimately ripoffs, the ever-renewable fantasy that we can be in on a trick first, that we can prosper through savvy arbitrage rather than sell our labor at a loss. They seem to offer products without the conventionally necessary production processes, which is another way of saying that they present a commodity fetish in an intensified form, hiding social relations in a more deceptive form of reification. Image generators depend on labor concealed in the form of data, their output obfuscates the social relations that went into how that data was collected and sorted and are, in that sense, pure ideology.

Gimmicks, Ngai argues, evoke criticality to neutralize it. “The moment in which the gimmick arouses critical response is … simultaneously a dissipation of criticality. Why continue paying attention to that which you’ve just judged as undeserving of attention?” The expanded Vermeer image serves to placate different audiences in different ways: Its banality reassures artists that the technology is not coming for them, while its gee-whiz appeal to the art-indifferent suggests to them that it will ultimately make art irrelevant.

Artworks of the past, these expanded images seem to suggest, will be assimilated, overwhelmed, and finally buried, along with the habitus once cultivated to “appreciate” them. Instead, machines will adapt to appreciate you, finding or generating images that appeal to your intrinsic specificity as a unique individual. In other words, I think that TikTok’s For You Page and AI art — my two hobbyhorses of late — are set to converge at the same point, positing an audience that can readily be flattered into a kind of compulsive passivity, easily brought to believe that imaginative effort is a matter of waiting to see how machines try to figure out what you want. Everywhere I turn, the field expands; more content magically emerges to plead for my attention, constituting my sense of it for myself in the process. I never knew I had so much attention to give.

Individually, these efforts fail; I doubt that anyone becomes fully alienated from their creative capacity or from the pleasures of imagining as a deliberate process. The novelty of AI-generated images quickly exhausts itself. No one prefers VR to reality. But collectively, algorithmic prediction and generation produce a convincing sense that there are other people who are what the algorithmic systems imply, and that it is becoming normative to surrender to those systems despite their manifest inadequacy. Why else do Twitter users care what is “trending”? Why else do people complain about platforms being “boring”? These are signs that you suspect the platform is thinking for other people, the arrivistes (if not for yourself), and generating an instantly consumable experience of “interest” in itself, of urgency and investment that doesn’t require an internal impetus. Recognizably “viral” content, which is the product of algorithms as much as anything AI creates, conveys a feeling of momentum in the abstract, a sense of “interestingness” as implied circulation and participation by everyone and no one. When I see this stuff, I sometimes imagine a “This person does not exist” laughing at it somewhere.

Feeds themselves can seem to propel us by the force of their own form, though inevitably there comes a moment when scrolling no longer feels like getting caught in the zeitgeist’s gale but instead just feels like scrolling for its own sake. The tension between wanting to be the person the algorithm thinks you are and wanting to resist being so predictable becomes unsustainable, and you find that you yourself have become the person who does not exist.

I don't have much to add to this but I really think you've provided a beautiful framework to understand and describe the dissatisfaction of "the feed" versus the experience of going to a real art show, even a terrible art show.