The signal of compliance

“Messages are themselves a form of pattern and organization,” cyberneticist Norbert Wiener writes in The Human Use of Human Beings (1950). “Indeed, it is possible to treat sets of messages as having an entropy like sets of states of the external world. Just as entropy is a measure of disorganization, the information carried by a set of messages is a measure of organization … That is, the more probable the message, the less information it gives. Cliches, for example, are less illuminating than great poems.”

Generative AI seems to have been developed on the opposite principle: that cliches are more illuminating that less probable forms of communication, and we need better and better technology for turning poetic text into something more prosaic and average. Text must be understood as probabilistic but not fundamentally undecidable or multivalent: Every attempt at communication should be treated as trying to communicate one specific thing, and machinic decoders should be capable of saving us the time of working out what that one thing most likely is for any given piece of text.

Hence the impoverished view of the purposes of language on display in this tweet:

For chatbot developers, all communication is bullet points — or perhaps more accurately just bullets, which need more efficient targeting to hit with the maximum payload.

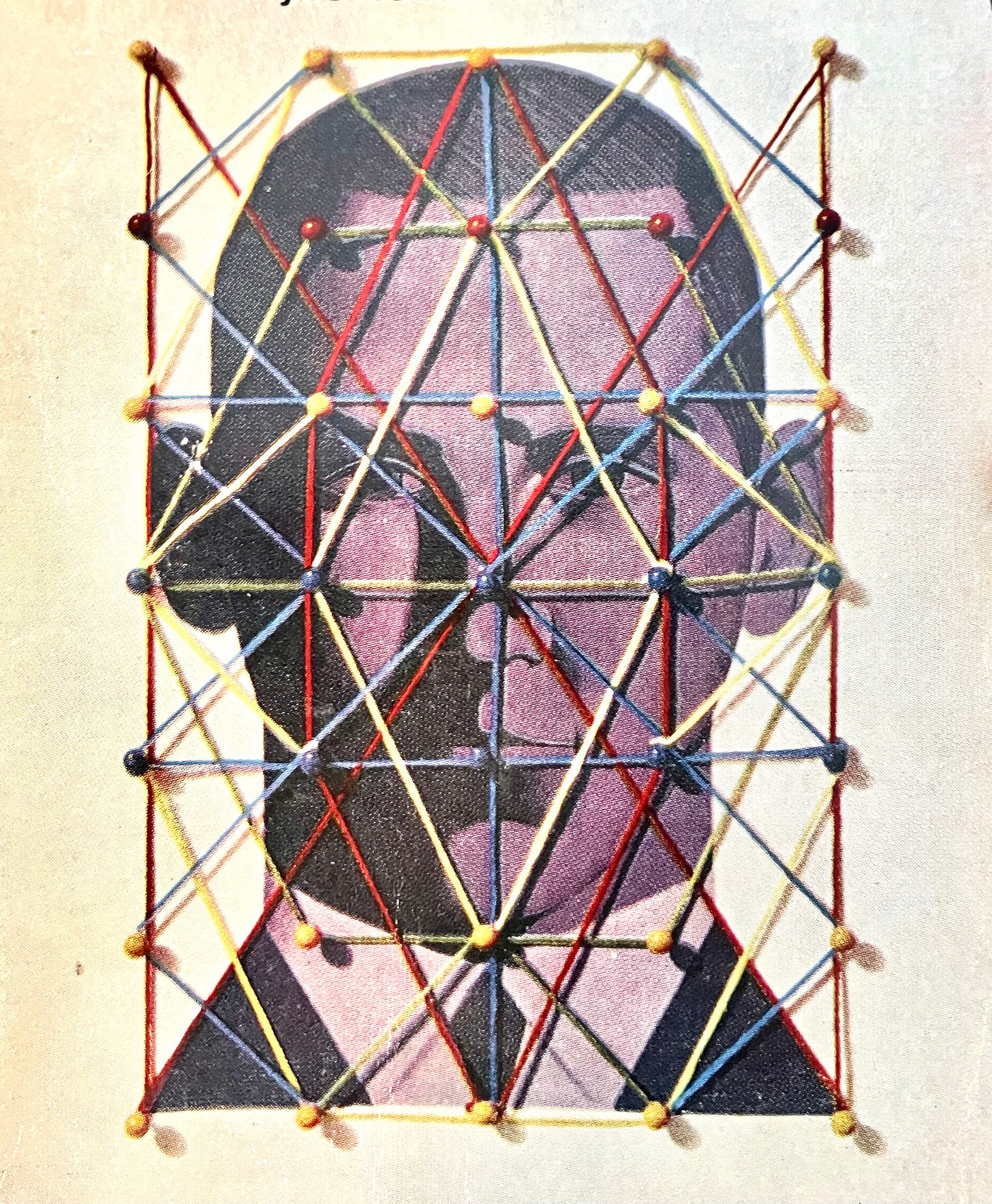

Wiener, who hit upon cybernetics while developing targeting systems for anti-aircraft weaponry, tends to represent communication as no more than issuing commands, an attempt to control whatever you are communicating with, be it a machine or a person. “When I give an order to a machine,” he writes, “the situation is not essentially different from that which arises when I give an order to a person. In other words, as far as my consciousness goes, I am aware of the order that has gone out and of the signal of compliance that has come back. To me, personally, the fact that the signal in its intermediate stages has gone through a machine rather than through a person is irrelevant and does not in any case greatly change my relation to the signal.” When you are giving orders, he suggests, you are always talking to machines.

When code is your model for ideal speech — when order-giving is all you want to do — you’d rather be talking exclusively to machines, which reliably provide the “signal of compliance.” Short of that, you’d hope to be talking always at least through the filter of machine processing: having a machine process your bullet points into output that I can direct my machine to process. Direct communication without the intercession of machine processing could lead to a dangerous ambiguity, tending toward a kind of unpredictable collaboration between human minds the product of which could not then be properly assigned as the property of one or the other. Why share meanings when you could issue commands instead?

Generative AI is coming along to help shore up the status of language as a form of order-issuing, of prompting, and to erode the possibilities that it can serve as a medium of intersubjectivity, a way to explore the conditions of other minds as not compliant but free, and worth communicating with for precisely that reason. AI obviously treats language as if minds were superfluous to its operation; its developers seem to assume that everyone wants to be similarly liberated from the imposition of other people’s minds and their intentions — the possibly that their signal is your noise.

Wiener frequently evokes Einstein’s maxim that “God may be subtle but he isn’t mean,” which he interprets as the scientist’s faith that nature doesn’t lie, doesn’t shift itself to protect its secrets. “Nature offers resistance to decoding,” Wiener explains, “but it does not show ingenuity in finding new and undecipherable methods for jamming our communication with the outer world” — that is, of properly interpreting empirical conditions. “In control and communication,” Wiener writes, “we are always fighting nature’s tendency to degrade the organized and to destroy the meaningful,” but at least it’s not doing it on purpose. Humans can work unilaterally against nature to preserve our localized sense of how it should be ordered.

This attitude — that it’s easier to master passive nature than a sentient enemy — can be detected in certain technophile fantasies about large-language models, which are presented as language purified of the devilish capacity of another speaker to try to deliberately deceive, bluff, or thwart the maximum efficiency of information transfer. Instead of having to navigate other people’s intentions in and through language — and along with it the possibility that they might have a worldview that doesn’t conform to your own, which you could understand as their trying to destroy meaning — you can just navigate language as if it were a medium in which other people were reduced to statistical “laws of nature” that have been empirically established. That way, you can preserve your sense of unilateral agency (you transcend such laws by virtue of your freely commanding the machine) and pretend that your handling language that way is an egoless effort at reversing entropy — just helping “organize the world's information and make it universally accessible and useful,” as Google’s mission statement would have it.

But for all Wiener’s treatment of information as essentially a quantity and communication as nothing more than programming, he also despairs about a heat death of the cultural universe as the world decays into “drab uniformity.” In describing information as subject to entropy, he sometimes seems to drift into presenting information as entropy, as though entropy were the only message the universe has for us. Contemplating the grand scheme of things, he offers cheerful passages like this one:

Again, it is quite conceivable that life belongs to a limited stretch of time; that before the earliest geological ages it did not exist, and that the time may well come when the earth is again a lifeless, burnt-out, or frozen planet. To those of us who are aware of the extremely limited range of physical conditions under which the chemical reactions necessary to life as we know it can take place, it is a foregone conclusion that the lucky accident which permits the continuation of life in any form on this earth, even without restricting life to something like human life, is bound to come to a complete and disastrous end …

In a very real sense we are shipwrecked passengers on a doomed planet. Yet even in a shipwreck, human decencies and human values do not necessarily vanish, and we must make the most of them. We shall go down, but let it be in a manner to which we may look forward as worthy of our dignity.

Is ChatGPT worthy of our dignity? I don’t think there is a single time I’ve used this new generation of generative AI for text where I haven’t felt a low-level embarrassment. It’s not the sort of embarrassment I feel when I look online for crossword-clue answers, or when I watch garbage TV — there is nothing particularly entertaining in it, no puzzle it is helping me solve. It’s more like I am brought to imagine having to be content with the mediocre replies it has to everything, its capacity to turn any imaginative query into a rote and joyless five-paragraph essay, its tendency to push me to spend mental energy trying to trick it into being interesting instead of concentrating on something that is actually interesting — which manifests as a kind of resistance to immediate comprehension that chatbots don’t offer. The chatbot is lulling me into thinking there is some sort of valuable knowledge for me in learning how to get anything useful out of it, when really I am merely adding value to the chatbot, refining its simulation and revealing more data about myself for the company that administers it.

With earlier text generators, I used to have fun parsing their replies to my prompts; they would read like flarf poetry, with implausible sequences of sentences and turns of phrase that felt like no human would ever have come up with them. I would ask for a list of the best Beach Boys songs and they would produce poetic gems like these. ChatGPT almost never does that. It generally produces turns of phrase that are all too familiar. No matter how absurd my prompts are, it ends up producing about what I would have expected, except slightly more tedious. Even its efforts at generating student essays are conspicuously terrible.

“The prevalence of cliches is no accident, but inherent in the nature of information,” Wiener writes. One can see generative AI, which produces cliches at an industrialized scale and scope, as the result of treating language as no more than information — it is an effort to impose that view on humanity — resulting in a world in which “nothing new ever happens.” In relentlessly making noise that passes for signal, and undermining the means by which one can tell the difference, Generative AI promises to be an entropy engine.

Wiener makes the very modernist-sounding claim that “in the arts, the desire to find new things to say and new ways of saying them is the source of all life and interest.” He contrasts this with “when there is communication without need for communication, merely so that someone may earn the social and intellectual prestige of becoming a priest of communication” — which puts in mind the new problem of publications being “flooded” with AI-generated submissions. “It is as if a machine should be made from the Rube Goldberg point of view,” Wiener writes, “to show just what recondite ends may be served by an apparatus apparently quite unsuitable for them, rather than to do something.” Who would bother to use such a machine, let alone make it?

“The dominance of the machine presupposes a society in the last stages of increasing entropy, where probability is negligible and where the statistical differences among individuals are nil.” Wiener claimed. “Fortunately we have not yet reached such a state.” To rid the world of those nettlesome statistical differences between individuals, we can take the tool they use to try to express them, language, and work to eliminate its contingencies. We can take apart the Tower of Babel brick by brick until no one can possibly say anything that will confuse us.